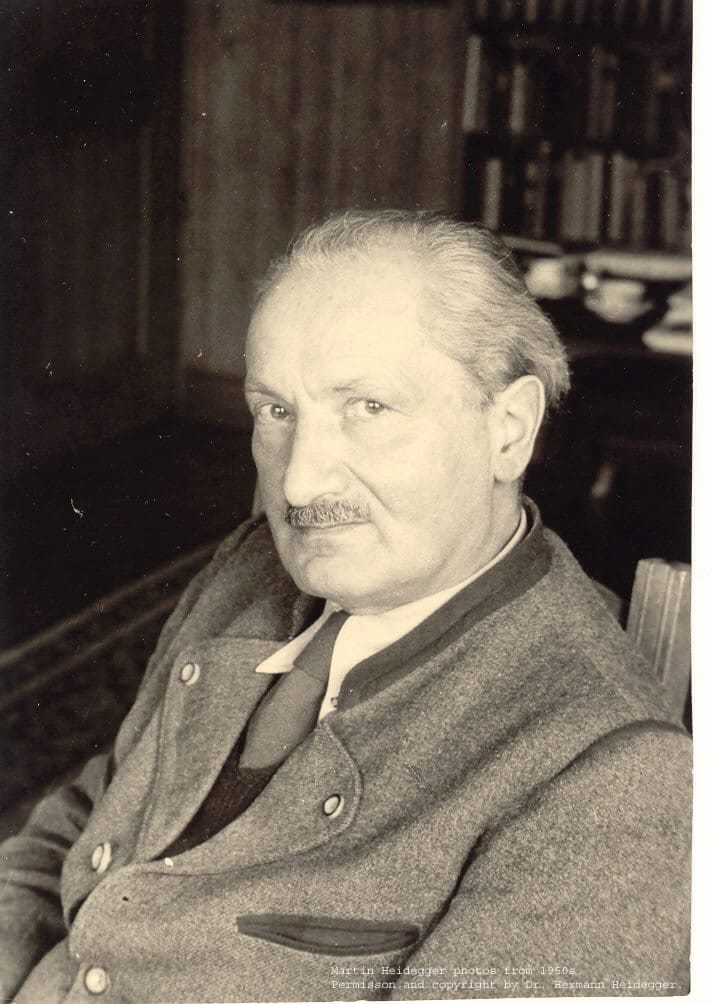

Why Heidegger was not an existentialist

Heidegger’s concern was the phenomenology of the world around us. Sartre’s concern was the battle for existence.

Welcome! This post is free. If you are a free subscriber, consider an upgrade to support my work and view all posts in this newsletter. Thank you for being here!

Perusing my previous post below….

…. I realized that one might misinterpret the thesis as making Heidegger out to be an existentialist. I want to clarify this thesis and remove any notion that he was. Heidegger is often referred to as an existentialist even though he himself rejected the categorization.1 He even parted ways with Jean-Paul Sartre over the latter’s lecture, Existentialism is a Humanism where Sartre posited the fundamental existentialist principle that existence precedes essence.

The question is only complicated because there are two kinds of existentialists. There are, on the one hand, the Christians, amongst whom I shall name Jaspers and Gabriel Marcel, both professed Catholics; and on the other the existential atheists, amongst whom we must place Heidegger as well as the French existentialists and myself. What they have in common is simply the fact that they believe that existence comes before essence – or, if you will, that we must begin from the subjective.2

The specific point of concern in my previous post is, “That the tree ‘is’ (aletheia) is the primordial inceptual ground preceding any logical, metaphysical notion of ‘treeness’ (metaphysics).” This assertion sounds like I am saying the same thing as Sartre when he says, “that existence comes before essence.” However, to interpret the statement in this manner reflects a misunderstanding of what Heidegger means by “is” preceding essence (metaphysics) and why so many others claim he was an existentialist.

The parentheticals in my statement are important clarifiers. Rather than meaning Sartre’s “existence precedes essence,” the “is” (aletheia) of the tree precedes its essence (metaphysics) in phenomenological givenness. The point is aletheia’s (unconcealment’s) relationship to the science of metaphysics, not existence’s relationship to essence. Heidegger is not saying that the essence of treeness is left to be worked out or interpreted as we wish. A tree can only be a tree because essence comes before existence, not the other way around. Heidegger is not concerned with that specific debate. Granted, Heidegger is not a metaphysician, but his interest is in demonstrating how the science of metaphysics, whatever one thinks of the existence and essence debate, has hidden over and forgotten about the Being of beings from whence metaphysics is derived. Givenness comes from Being, not from metaphysics, even if we agree that metaphysics is essential. Heidegger’s point is not that existence precedes essence in accordance with the existentialist mantra but that Being precedes essence in accordance with phenomenological givenness.

The majestic tree perfectly proportioned in the serene meadow “gives” us much more than “treeness.” The tree is the perfect piece of the puzzle that brings the entire panorama together into one breathtaking view. What the tree gives us does not deny the metaphysics of “treeness”; it simply precedes that treeness in phenomenological living-in-the-world awareness. We do not walk to the crest of hill overlooking the panorama and first assemble the metaphysical essence of the tree with the other components of the meadow. Phenomenologically, we walk to the crest of the hill and receive the truth, beauty, and goodness of the panorama and the tree’s place in it. This phenomenology is what the tree “gives” us. As those living-in-the-world with the tree, we first receive that givenness.

Heidegger’s concern was the phenomenology of the world around us. Sartre’s concern was the battle for existence. These are quite different emphases. Thus, “That the tree ‘is’ (aletheia) is the primordial inceptual ground preceding any logical, metaphysical notion of ‘treeness’ (metaphysics)” is not to be interpreted as an existentialist principle but as a phenomenological one. The majestic tree primordially gives us a contemplative masterpiece before our eyes, not “treeness.”

"To be sure, Heidegger himself once said that he is not an existentialist, and that he would like to restrict the meaning of the term "existentialism" to the philosophy of the French writer Jean-Paul Sartre." Von Rintelen, Fritz-Joachim. The Existentialism of Martin Heidegger.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism Is a Humanism. 1956,